This month’s worth of books was great, as usual, but there is one standout among them that I’d like to take a little more time with because I feel so strongly that it should be read by every American citizen. That book is North Korea: Another Country by Bruce Cumings, and I cannot stress enough that everyone should read this book, regardless of if you know a damn thing about Korea or even East Asia in general. It’s weird to start out a post like this but I wanted to draw immediate attention to this book in order to prevent its importance from slipping through the cracks amidst the four other books I read this month.

That’s not to say the others weren’t great! They were. I’ve yet to read a book this year that I didn’t like (maybe because I’m picking them out myself 98% of the time?). But please, if you don’t read anything else on this post, read about this book. It’s just that good.

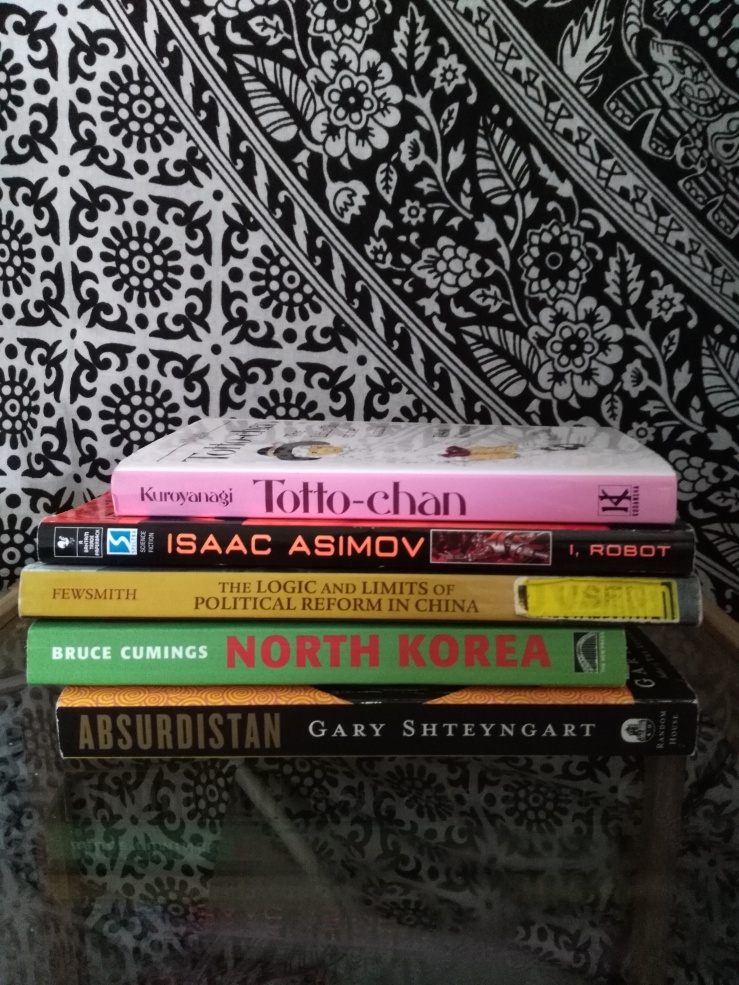

May reads, in chronological order:

Absurdistan | Gary Shteyngart

My first Shteyngart book was Super Sad True Love Story and it blew me away. I couldn’t imagine anyone writing a more pertinent political and social satire befitting the modern day (until I read Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, which in my mind is equally as masterful). Absurdistan was written prior to Super Sad, and follows the antihero Misha Vainberg, a Russian Jew, through his efforts to leave Russia and embrace American multiculturalism (which, for him, primarily refers to black culture, and not much else). As he’s trying to make his way to New York City, he makes his first stop in Absurdistan, a former Eastern Bloc country (though obviously made up for this novel). Upon arriving, a civil war breaks out, and Misha’s great American escape plan becomes a bit more muddied as everyone else concerns themselves with being on the winning side.

While this book was hilarious, and true to the Shteyngart style that I became so enamored with after Super Sad, I have to admit I felt like some of the satire went over my head. I think anyone from Russia or familiar with the lifestyle and culture of Russia and/or the former Soviet satellite states might have been able to enjoy this book more than I did, and since Shteyngart is a Russian immigrant, it makes sense that he would write something like this. Super Sad was more relatable (I hate using that word but I have no other way of saying this) for me, which is probably why I enjoyed that book more than Absurdistan. Nevertheless, this novel is worth a read for anyone who enjoys political/social satire.

North Korea: Another Country | Bruce Cumings

Now that I’ve really hyped this book up for you, here comes the “why.” In America, we get one side of the story when it comes to North Korea: our over-simplified, sensationalist account of why this country hates us and why we hate them. We berate the regime for their human rights abuses, their extreme ideology, the apparent hereditary succession of power, and herald these transgressions as our reason for not engaging them (all while we make oil and arms deals with the Saudi monarchy…). Most of all, we panic about their nuclear weapons program, all while laughing at the “ridiculousness” of their “insane” “child-like” dictator, Kim Jong-un (see The Interview). Cumings, an esteemed scholar of Korean history and the current Department of History Chair at the University of Chicago, essentially asks us all to empathize, not sympathize, with North Korea, and he claims the necessary ingredient in this recipe for understanding is a knowledge of Korean-U.S. history throughout the 20th century. Primarily, the Korean War.

When I was reading this book, and when people asked me what it was about, I asked them if they knew much about the Korean War. Almost all of them (except for my boyfriend, who has studied East Asian politics for years) said they didn’t. When I told them Cumings refers to it as “the forgotten war,” they all agreed. In my own experience, I can honestly say that if I hadn’t taken an interest in East Asian politics, I too would probably know next to nothing about the Korean War. It was never really discussed in any of my history classes before college. I knew it happened, but I couldn’t have told you when, or why, or what really happened on that peninsula. Yet I could talk pretty comfortably about WWI, WWII, and the Vietnam War, even though we dropped more napalm in Korea than we ever did on the Vietnamese. We committed heinous war crimes that we were never held accountable for. No one ever talks about it. At least, no one ever talks about it here, in America. In North Korea, the Korean War is still fresh on their minds. It informs every decision the DPRK’s government makes in terms of relations with the U.S. After all, the war never actually ended. An armistice was declared, but technically, it’s been going on for decades.

Obviously, I could talk about this issue all day, but I’m nowhere near as qualified or eloquent or witty as Cumings is, so I’ll leave it to him to tell the rest. This book is one of the most level-headed, unemotional, unbiased analyses of our relationship with the DPRK, and despite being written in 2004, before Kim Jong-un took power, its message is just as relevant (if not more so) today. Cumings encourages dialogue over saber-rattling, understanding over nationalism (disguised as patriotism), and discourages a reliance on information regarding the DPRK from any of the major news outlets. It’s a quick read as far as history books go, and well worth your time.

The Logic and Limits of Political Reform in China | Joseph Fewsmith

Okay, I’m no chump, I know this book probably sounds immensely boring, but if you’re interested in Chinese politics it’s probably one of the best books out there surrounding the topic of potential democratization in China in the near future. Plenty of China-watchers want this to be so, and unfortunately, Fewsmith’s analysis doesn’t really bode much hope in that arena. He looks at case studies of democratic practices that have popped up (experimentally) in small villages throughout China, as well as inner-party democracy, and tries to find evidence of the institutionalization of these practices. It is not enough for him that they are successful; he wants to see if they’ll last.

I’ve read several articles by Fewsmith but this is the first book of his I’ve read and I thought it was brilliant. He takes a rather technical issue and makes it digestible, and his argument is solid. It’s not an optimistic book if you’re crossing your fingers for China’s democratization, but I think he’d probably agree with fellow China scholar Andrew Mertha in that if you’re looking for liberalization or democratization, you might just be missing the forest for the trees. There’s a larger picture here, and while China may not be heading towards democracy, that doesn’t mean it’s not changing in other interesting ways (see Mertha’s incredible book China’s Water Warriors for more on this subject).

I, Robot |Isaac Asimov

Here’s a book I’ve been meaning to read for a while and never got around to it until now. The copy I have looks like its marketing towards young boys (glossy neon orange cover, cheesy drawing of a robot, silly tagline, etc.) and while this book could certainly be read and understood by children, I’m not sure I’d call it children’s lit. Asimov’s thought experiments are fascinating enough to keep a child’s attention but harbor a complexity that adults will appreciate. The book is composed of several different stories told within the context of an interview with a woman named Susan Calvin, a “robopsychologist.” I think most people are familiar with the premise of this book (maybe from the movie of the same name? Although I’ve heard they’re not really much alike) so I’ll keep this brief and end this with a recommendation: you don’t have to love science fiction to enjoy I, Robot. The issues that arise in the book are universal questions of humanity; questions that are already relevant in an age of growing AI technology which will only become more pressing as time goes on.

Totto-chan | Tetsuko Kuroyanagi