Friends, it’s been a whole year since I started this project of mine, and this is where I bring it to a close. This was the first time in my life I have ever taken care to record and review each book I read. It was my resolution for the year, and one I hoped would help me keep up the kind of mindful and diligent reading I was so used to in school. And, ultimately, I think it worked. Throughout 2017, I read 54 books and wrote reviews for each of them here (though not always in a timely manner).

I had originally debated doing this project privately, in a journal or a Word doc. Ultimately, I’m glad I didn’t, because I ended up getting a lot of positive feedback from friends and family about it. People told me that they read a book I had reviewed here based on my review, or that I had inspired them to keep a list of what they read. Some people saw that I reviewed a book they loved (or hated) and struck up a conversation with me over it, and some gave me book recommendations based on something that appeared in one of my “Between the pages” posts. I ended up connecting with people over books, and not necessarily just people I was close with prior to this project. If you were one of those people, or even if this is the first monthly reads post of mine that you’ve read, thank you. You added a new dimension to my project, and made it more fulfilling than I could’ve imagined.

As for continuing the monthly reads posts into the new year, I’ll admit that it’s not a priority of mine. 2018 is already shaping up to be a very different year, and if everything works out the way I hope it will, I’ll be busier. These monthly reads posts are pretty time-consuming; they take at least a day, or sometimes two, and while I was able to make that work with my schedule last year I’m just not sure I’ll be blessed with that much free time this year. That being said, in order to keep the spirit of my resolution alive, I’m thinking I might post something more like a “book of the month” instead. If that sounds good, or you have a better suggestion, let me know! I certainly won’t be updating this blog on the progress of my 2018 resolutions (more flossing, less sugar).

I was also tossing around the idea of doing a sort of “awards” post for the books I read last year, ie. the best book I read, the worst book I read, the funniest book I read, the most life-altering book, etc., so we’ll see if I get around to doing that. I’m only giving myself until the end of January to do that, so you’ll soon find out.

Alright! Now that I’m done rhapsodizing, I’ll get back to business for the last time.

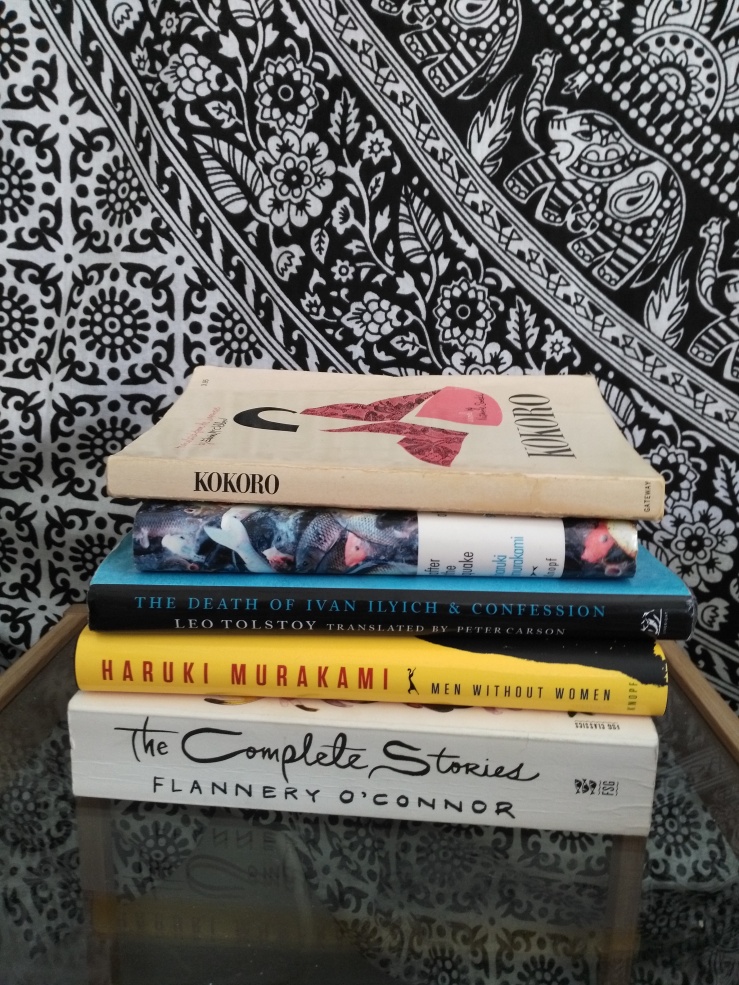

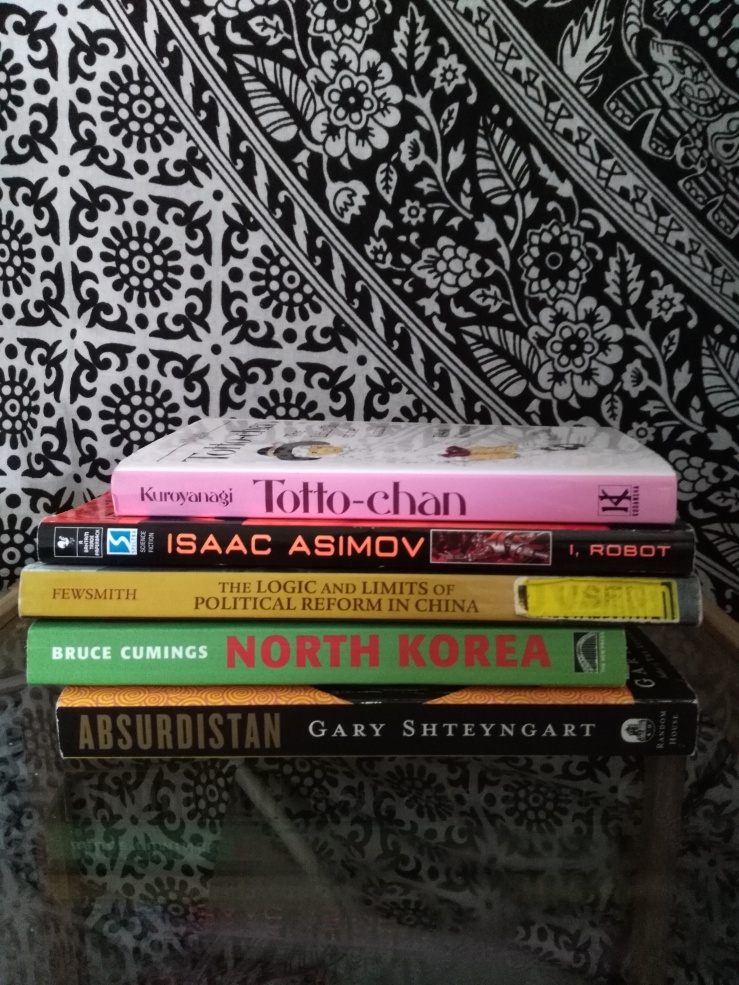

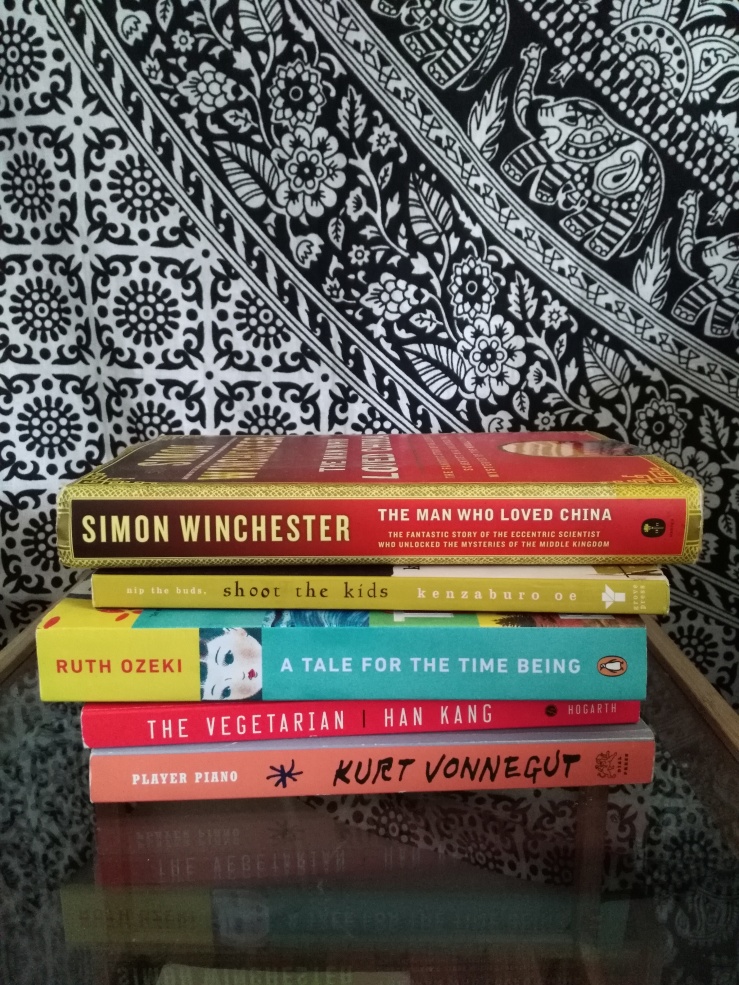

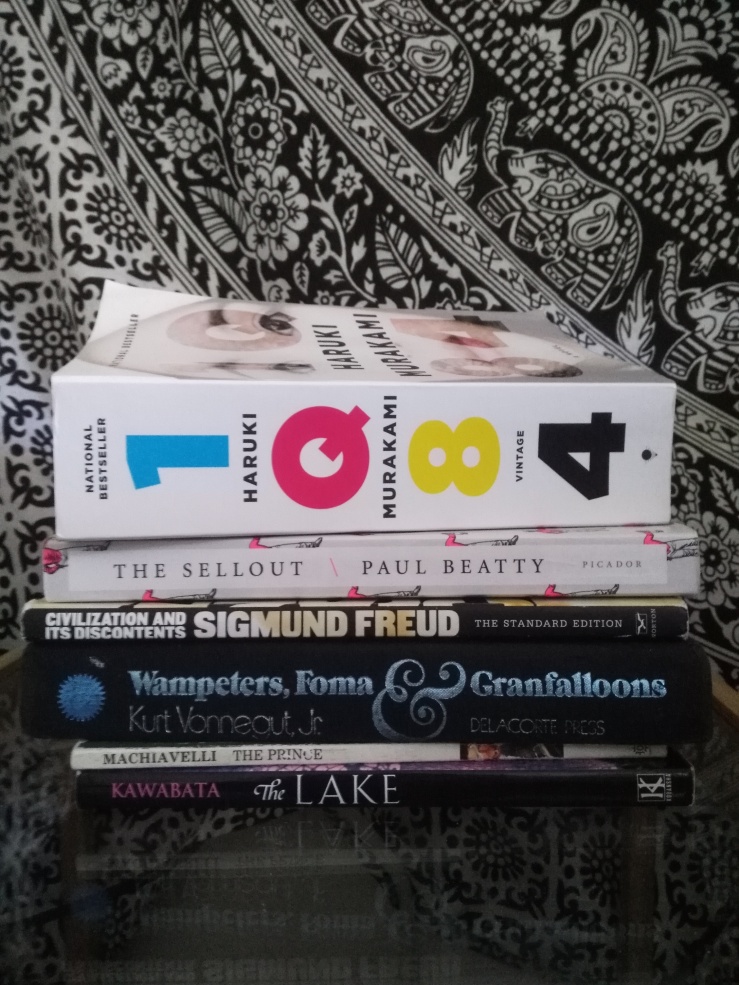

December reads, in chronological order:

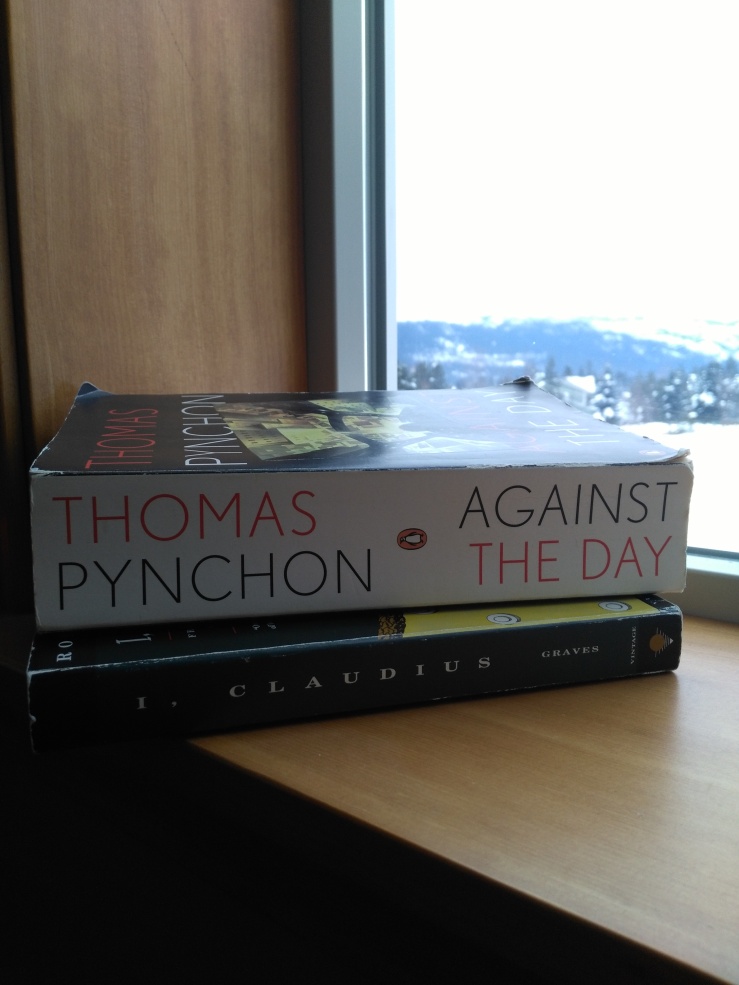

I, Claudius | Robert Graves

I was on a bit of a historical fiction kick when I picked this book up out from under the back seat of my car, where it must’ve fallen during one of the various times I’ve moved in the past year. Widely considered to be a classic and a prime example of the feats of this genre, I, Claudius is the first of a two-part series based on the autobiographical accounts of Roman Emperor Claudius, who ruled from A.D. 41-54. If nothing else, this has got to be one of the most well-researched pieces of historical fiction out there, which is saying something for a genre that requires it. It’s a dense work, and it was hard for me to really get into this book at first, but when I did get going it was hard to get back out. I, Claudius covers Claudius’ life from early childhood up to the assassination of Caligula and his resulting ascension to the throne, where the second book picks back up. I have no idea how detailed Claudius’ autobiographical works are, but I imagine Graves had to do a lot of creative work here filling in the gaps and understanding relationships between these fascinating and important historical figures. Claudius is one of maybe three characters who are actually likeable, the rest being power-hungry, murderous, deceitful, disgusting, or all of the above. If you enjoy historical fiction or have ever been interested in ancient Rome, this is a must-read.

Against the Day | Thomas Pynchon

I started the year with Pynchon (Gravity’s Rainbow) and I ended the year with him too, by no accident. As you may remember, or maybe I didn’t disclose too much in my review, I can’t remember… as you may remember, I struggled with Gravity’s Rainbow. And yeah, I’m not the only one, and I’d be really suprised to find a single person (Pynchon included) who didn’t struggle with it either, but I felt like that book kicked my ass. 70% of the time I had no clue what was happening, or who the characters were, and even though I was pretty sure I was supposed to feel that way and even though I let go pretty early on, I still felt like I was really missing something. Knowing full well that people take entire classes on this book alone, I realized I probably would’ve gotten a lot more out of it had I been reading it with peers (and a very patient professor). And since not many people have the time for or interest in reading a 1,000+ page novel in a month, I decided the next best thing I could do (besides read hundreds of analytical essays on the damn thing) would be to… well, read another Pynchon novel. Obviously, it took me nearly a year to amass the energy and willpower necessary, but I knew when I was shopping for $1 books at a local sale and saw Against the Day in all its phonebook-esque glory that this was how I’d be spending the remaining days of 2017. Remaining hours, I should say– I finished the book at 11:30pm on the 31st.

As it turns out, Against the Day was leaps and bounds more accessible than Gravity’s Rainbow. Sure, there were a lot of characters, but pretty much all of them are recurring and you get to know them fairly well by the end of the novel. Of course, I didn’t always know what exactly was taking place, especially in regards to the “Icelandic spar”: a material with “double-refractionary” properties that literally clones a person, from what I could make out. But! I did have a good grasp on what was going on, hmmm… 90% of the time, I’d say. And sure, there was weird sex, but compared to Gravity’s Rainbow it was vanilla as a golden Oreo.

The main characters in the novel are four siblings: Frank, Reef, Kit, and their sister Lake Traverse. Their father, Webb Traverse, is an anarchist outlaw known for dynamiting mines in support of unions. One day, he’s murdered by a couple of hired hands paid by Scarsdale Vibe (think Rockefeller level rich, and just as greedy). Frank and Reef set out to avenge their father’s death, while Kit leaves for college, and Lake knowingly marries one of her father’s murderers. Most of the story follows these character’s lives as they travel from Colorado to the ends of the earth, in some cases, meeting — you guessed it! — a whole host of other quirky characters along the way. Oh, and there’s this group of guys called the Chums of Chance, who fly around the world in an airship, carrying out the wishes of… people from the future? I think?

I gotta be honest: I’m not done trying to figure this book out. It revolves a lot around the anarchist movements that really caught on during the turn of the 19th century (when the novel takes place), as well as the new technological advancements (namely, electricity) that were revolutionizing the world, and the ways in which World War I changed war forever and foretold what was to come. The characters of the novel are all either running after something or running away or both. And that’s just the surface. Really, if you ever get around to reading this book, please let me know so we can talk about it. In the meantime, I’ll give you my favorite excerpt from the whole book to hopefully entice you into taking the plunge:

“It went on for a month. Those who had taken it for a cosmic sign cringed beneath the sky each nightfall, imagining ever more extravagant disasters. Others, for whom orange did not seem an appropriately apocalyptic shade, sat outdoors on public benches, reading calmly, growing used to the curious pallor. As nights went on and nothing happened and the phenomenon slowly faded to the accustomed deeper violets again, most had difficulty remembering the earlier rise of heart, the sense of overture and possibility, and went back once again to seeking only orgasm, hallucination, stupor, sleep, to fetch them through the night and prepare them against the day.”

So, you sold yet? I’m happy to say this book made me resent Pynchon less, and I love that I’m still trying to figure it out days after finishing it. It was the perfect way to bring the year full-circle (and restore my ego somewhere closer to its size pre-Gravity’s Rainbow).

Thank you for following “Between the pages”! Happy New Year — here’s to more mindful reading.